Mission, evangelism, outreach – three words which ultimately mean the same thing: going out and sharing the Gospel.

There are some differences, though: mission conveys the (literally apostolic!) idea of being sent, evangelism has a focus on the nature of what is being shared – the Bible – and outreach suggests the existence of a structure to go back to. The differences between these three leads to a major question: why are we doing this? What leads us to “do” mission? What do we share? And with whom?

Yes, the Great Commission instructs us to go and teach all the nations. And that’s very well. But if it is our sole motivator to go out and share the Gospel, then not only does evangelism become something we just do, but the message we share itself becomes stale. We end up needing to be right, and we end up needing to persuade others that we are.

We start to develop standard answers to deep and personal questions, for instance on creationism, eschatology, homosexuality, suffering, science, etc. – and these are answers we need to have ready, because we can’t be seen to “not have it sorted”.

Woe to us if we end up like that. If we end up reciting the same message to all, with just some tiny alterations in style. Because the fact is the Word is alive to all of us. It grows, it interacts with the people who hear it, and it changes us. The point is, it has interacted with us (and still does). It excites us, makes us passionate.

For instance, I find that I come truly alive when I share some passages that really resonate with me (for instance the story of Gideon. Or John 15.) But every time I do, it is because I explain what this meant to me. How that is relevant to me (and, I hope, it can be to those I share it with). I find that much harder to do when I’m talking to non-Christians.

I’m not sure why, but I think there are three main reasons:

- I feel the weight of responsibility. What if I say something wrong and shut that person off to the Gospel?

- I’m representing some organisation to an outsider – and personal beliefs shouldn’t come into that, surely.

- I need to be seen to have it all sorted. If not, my message is worthless.

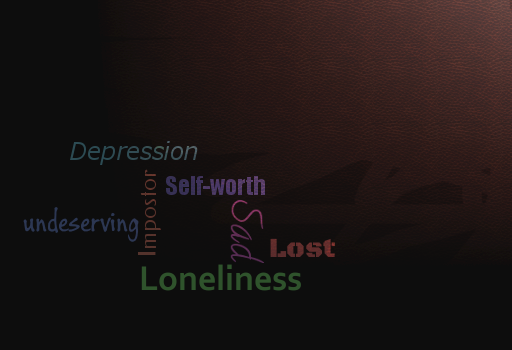

And so, when I started taking part in evangelism events, it soon became an intellectual exercise – one that goes both ways, and which allows me to probe some questions myself too; but still, one that involves the mind when I’m talking, and the soul only afterward when I’m praying. I find myself pigeon holing people into categories, which stops me from truly engaging with them.

The Psalmist warns us:

Malicious witnesses rise up; they ask me of things that I do not know.

Psalm 35:11 (ESV)

Should we then stop going out to share the good news? Stop opening ourselves up to these malicious witnesses? Of course not. But we should be wary of these malicious witnesses; and of the focus they have on asking us things thatwe do not know. Rather than addressing the intellectual arguments as something we can get sorted for ourselves and explain on our own to others, and thus becoming falsely self-reliant and arrogant; we should focus on what we know.

What do we know? We know our story. We know how we got changed. We know how reading the Word excites us. How much Jesus matters to us. We know Jesus. What we do not know, is the apologetical arguments – not until we have made them our own. And even then, what we know is the story of how they became our own.

This is what we can share without risk of self-satisfaction and self-reliance. This, and this alone. The rest we must leave up to God.