“That wasn’t a sermon” – that’s a criticism I’ve heard about sermons a few times (including my own). We all have ideas about what a sermon should be. Why? What makes a sermon sermon-like?

The Oxford English Dictionary gives some ideas: it is, for our context, a talk on Christianity. In written form, it could then, be this blog. But this blog is not a collection of sermons – with the exception of two posts. Let’s read a bit further: it suggests sermons are long and tedious.

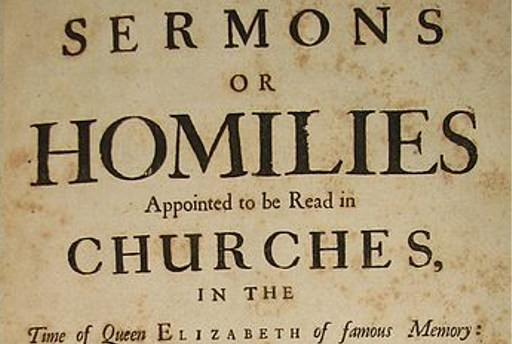

Image: Wikipedia (Public domain)

Maybe we shouldn’t complain, then, when we don’t hear a sermon. More seriously, though, there is one thing that makes a sermon a sermon: that it is given as part of a church service. In other words, that it has the label “sermon” all over it (after all, podcasts of sermons are still sermons). So if you heard it at church, it is a sermon. The thing is, a church service is a full and well crafted (hopefully) set of parts, whose aim is worship and edification. A church service is not simply a sermon with some padding around it, nor is it some liturgy with a homily thrown in the middle: it is a dynamic set with a purpose. So a sermon should fit into that set and lead the audience (and the preacher!) to be imitators of Christ, rekindle in them a passion for God and open their hearts. If that’s missing, then it might as well be a secular talk!

Bible based?

That a sermon is not “Bible based” is the big argument of those who say “That is not a (good) sermon”. As if being Bible-based were the only hallmark of a good sermon! Matthew Henry’s commentary is Bible-based – very much so, indeed – but it’s not a sermon. Because it is looking at the Bible as an object to be studied, rather than as a source that talks to us. Those last two word are important, because this is where we remember that a sermon takes place with an audience.

The most useful tip I’ve heard so far for sermon-writing is this: “Can you tell me in one sentence what you are trying to achieve with this sermon?” It’s not about what point we might be driving through the sermon, it is about recognising the transformative nature of a relationship with Christ and mediating that to the congregation, as best as we can.

Sometimes, that goes through close exegesis. Sometimes that goes through less Biblical sources – talking, say, about the Internet is hard to do when you’re Bible-bound. And so, as long as the aim remains firmly to get people’s hearts turned towards God, then I don’t think being Bible-based is a necessity for a sermon. In most cases, it helps. In some cases, it is even necessary because the sermon will be the only time in the week the congregation touches the Bible. Still, as a hard-and-fast rule, it detracts and leads to cherry-picking some verses to “make a sermon Bible-based”, when all the sermon does is drive a pre-determined point. And when that happens, well, it’s a bit of a scam.

So remember: a sermon takes place in a specific context. It is by that context that it can be judged – not independently of it. And sometimes, the surprise of a new type of sermon might do just what a sermon should do: refresh our love for God.