The Bible is, together with prayer, the way to learn about God and connect with Him. But its role is sometimes misunderstood. Here’s a short list of things I’ve heard about the Bible which quite frankly upset me – some because I think they don’t do justice to the Bible; others because I think they stop people from accessing it.

1. The Bible is just a reference book. One that we might look at if we want to decide whether getting a tattoo is wrong, or to find out about the life of Christ. If that’s the only way in which the Bible were to be read – simply as an authority – then a rulebook might have served better. Talking of which: isn’t that the Old Covenant approach? The Bible is the living word of God. It inspires us, it teaches us, it moves us and, essentially, transforms us.

2. There’s only one way to read the Bible. Of course not! There’s many ways to read the Bible. I’m not talking here about literal vs figurative interpretation; nor about how to take the cultural context into account. These debates are important, yes – but better left to others; and taking sides in this debate, to me, feels like turning the Bible into just a reference book. What I’m talking about is ways to let the Bible transform you. And for that, there’s plenty of ways. Tease out the general meaning of a passage – its direction, its structure, its rhythm; when it’s a story, identify with different persons in turn (yes, including Jesus) and feel what they’re feeling; etc. etc.

3. The Bible is boring. If you really think that, you haven’t read the whole Bible. Seriously, there’s bits of 2 Chronicles which are far more gripping, even from a storytelling perspective alone, than Game of Thrones’s most gripping. And these bits aren’t an exception – most of the Bible is just as gripping.

4. The Bible is exciting throughout; this myth can be followed with: “and if you don’t agree, you’re missing the point of whatever you don’t find exciting.” I personally don’t find the whole Bible exciting. Sometimes, it’s a drag because it’s boring. Sometimes it’s a drag because it’s depressing. Seriously, though, if you manage to get the first ten chapters of 1 Chronicles to look as exciting as John 15, then (a) you really have a heart for genealogies and (b) please share that excitement with us in the comments. Yes, most, if not all the Bible, points to Christ and is exciting for that reason. But just like any other book, there are bits that are a drag to read.

5. Bible verses can be used as ammunition to shut down an argument. This myth is also known as “Cos the Bible says so”, a phrase which has become one of my pet hates. If the Bible is the living word, then let’s treat it as such. Imagine you have an argument about the theory of relativity, and somehow you have Einstein or Eddington at your disposal. Do you simply get them to come and stand behind you, or do you let them speak? The Bible, as the living word, opens up conversations – it does NOT shut them down.

6. Reading the Bible is an easy habit to take on. This is not true. Like I said before, it can be a drag. And if on top of that, you live in an environment that only considers the reference book aspects of the Bible, you lack the motivation to do so – after all, not many people just take up a textbook regularly. Being reminded that it is a book that transforms us is far, far better a motivation to read it! But there are ways to help: I personally find reading plans extremely helpful; but I also find that once I have the dynamic going, it’s a pleasure. And yes, sometimes I lose that dynamic and it’s a drag again to get back into it. I’ll admit – I’m currently about a week behind on my plan and it’s not the easiest to get back into the daily reading habit.

7. If you don’t have a reading plan, you’ll burn in hell. Also known as “read your Bible every day or perish”. Folks, don’t read the Bible out of a sense of ought-ness, that’ll get you nowhere. Get started out of a sense of ought-ness, maybe – because otherwise you might never start. But don’t let that be your sole motivation:

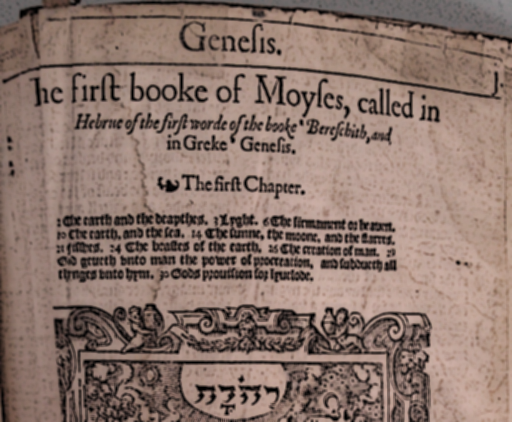

8. Only the KJV is valid for reproof, teaching etc. Yes, some people do believe that. I remember reading on a forum a while back someone claiming that Hallelujah was an English word that had been stolen by the Hebraic language. So, to clarify: the KJV is not the original text. It’s not even the earliest English-language version! Yes, I’m being flippant here; but have you ever looked down on others for the translation they use? Why would “KJV+NIV+ESV+NRSV” be the only valid set of translations?

9. Protestants know the Bible off by heart. We don’t. We know some verses, but definitely not all of them.

10. Catholics don’t read their Bible. Seriously, I’ve heard that a few times, and it annoys me to no end; so let’s make it clear: Catholics read their Bible just as much as Protestants do. And kudos to them for that – after all, they do have more to read ;-)