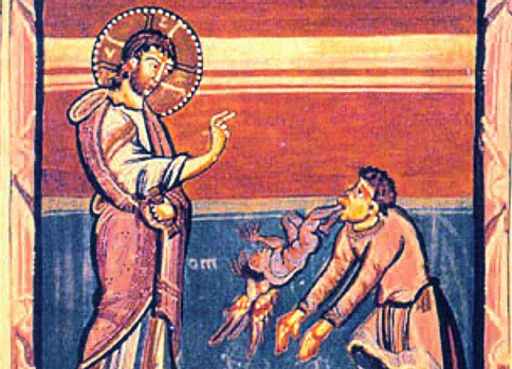

The Bible is full of instances of the supernatural. Demons. Healings galore, talking donkeys, water turned into wine. Visions. Forgiveness of sins; lives turned around.

Image: Wikimedia (Public domain)

You’ll note that I’ve included purely human events into the supernatural category. There is nothing natural about complete repentance (although we sometimes forget this and think we can repent in our own strength), yet in the case of Zacchaeus and of Paul, this happened both suddenly and in astonishing proportions. Yet we’re less uncomfortable with these events – we’re less uncomfortable with some types of healings, visions, and events affecting, primarily, humans. It isn’t because we are more familiar with ourselves – rather, it is because we do not know much, rationally, about our natural selves. It is easy, therefore, to treat any supernatural event as an unexplained natural event.

Common wisdom has it that where the territory of science progresses, the territory of faith regresses. This may be true of creation myths, but as far as supernatural events are concerned, the opposite is true. The more we know in science, the harder it is to consider that some of the miracles depicted in the Bible are not, actually, a consequence of natural coincidences. For instance, assuming the Legion episode was a case of epilepsy works only as long as we can imagine epilepsy has a carrier pathogen which can be transferred to the pig herd. Being kept in the dark allows us to accept the supernatural as part of the normal world order far more easily than knowing about it.

The vagueness that is prevalent in popular conceptions of mental health issues does not help. It is just as easy to dismiss an event as a consequence of psychological trouble as it is to dismiss it as a supernatural event. But whilst we can hope to be in control (through medical advances, for instance) of the former, the latter is, by definition, not controllable by natural means. So it’s unsettling. If we accept that there are supernatural events, it means that even our healthy selves can be affected by them. It means that we are no longer in control.

That loss of control – even though it was only an illusion in the first place! – is why I’m still fairly uncomfortable when the spiritual refuses to stay hemmed in to the spiritual and turns into supernatural events. I’m out of my depth when that happens. But rather than investigating it more deeply, I tend to either brush it under the carpet or leave it alone.

Discerning the supernatural from the troubling yet natural takes quite a bit of skill, I’m sure. But just as much as it can be disastrous to mistake the latter for the former, so can it be the other way around.

Yet I still feel uncomfortable even discussing these issues. I’m not sure that discomfort is a bad thing, but it should not keep me from envisaging the possibility of supernatural (including demonic) activity. What do you think?