A few weeks back, it was Trinity Sunday, also known as the occasion for heretical analogies. It is extremely difficult to grasp, intellectually, how one God can be three persons, and all the analogies that I know are flawed in some respect. This hilarious video points some of them out. Before going any further into the topic of the Trinity, I should point out that, in matters such as this (the mysteries of faith), we shouldn’t ever expect to fully understand; however, this does not mean we should not keep contemplating it. Indeed, as we do, we get closer and closer to God, in our understanding and in our lives. But as we do, we should not try to explain the Trinity, as though it were something we can grasp fully; rather, we should try to describe it.

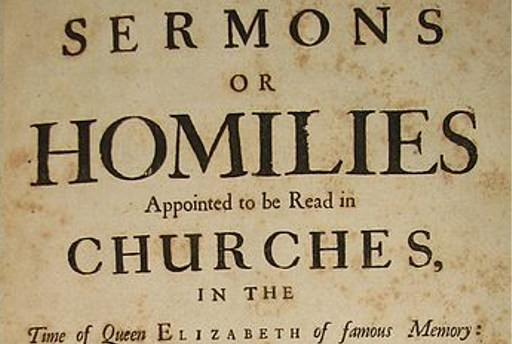

Painting in the public domain (full image on Wikimedia)

There are three persons (three “hypostases”): the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. A lot of our worship focuses on the Son (with the help of the Holy Spirit), and it is Christ we’re following. And so we focus more on the Son, and end up neglecting the other persons of the Trinity. While we tend to be aware that we don’t know that well how to picture the Holy Spirit, the same does not necessarily hold for God the Father. Yet, who is He?

There are three things to know about God the Father:

1. He is indescribable. Saying it right off the bat actually relieves the pressure, as we know we can’t reach the perfect description. He is greater than all of creation, and even if we had measured the mountains and the seas, we could not describe Him.

2. He cares for us, even though we are nothing before Him. This, in turn, implies two things: as our actions are naught too before Him, that this caring love is not dependent on what we do. Secondly, that His promise is greater than anything we could achieve ourselves. He will make us soar on wings like eagles.

3. We are called to be His children and to behave as such. This call to action is not one of obligation, but a mere expression of our identity as loved children of God the Father.

—

You can listen to the sermon, which (like the above summarising points) is based on Isaiah 40 and Matthew 28, by using the player below, or you can download the audio or read the sermon notes.

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.