It is no news that I love liturgy. Or rather, I love being excited about liturgy: I love the passion that still transpires through prayers crafted centuries ago. The Nicene creed has probably been said by billions of people (in various forms and languages) and is an example of such a powerful prayer. I’ll focus on one line:

For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven.

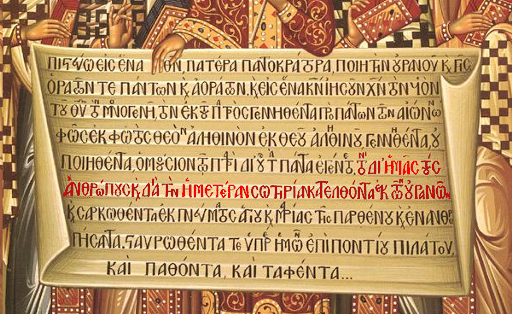

Icon of the Nicene Creed in the public domain

For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven! It’s not abstract! It’s not “For the world”, or “for humanity”. The original Greek actually starts with “For us humans” – making it clear that “us” is not simply a byword for an abstract concept, but something deeply and utterly personal and communal. The same goes for “our salvation”, where the Greek ἡμετέραν is the emphatic form of “our” (although, admittedly, this form is far more frequent than its non-emphatic counterpart ἡμῶν).

More than that: it is for us and for our salvation that Jesus came down from heaven. Jesus did not simply come to be nailed upon a cross and provide salvation. No, he came first for us. Redemption is not a cold, mechanical adjustment of a cosmic balance sheet. Penal substitution, without love, is nothing. There is a tendency, especially in evangelical circles, to focus too much on sin and thereby on the need for salvation through atonement. This focus is backwards: his love comes first. “For us” comes first, because it is only in the light of this love that the cross can begin to make sense.

The Nicene Creed does not say “For our sanctification and for our salvation”, either. The Incarnation is Jesus coming down from heaven, to meet us where we are. This isn’t about meeting the potential, sanctified person we will end up being – no, it is about meeting us in the here and now.

But the Nicene Creed does not stop at saying “For us” – it recognises the importance of atonement. “For us” is where Christ meets us, “for our salvation” is where he takes us. In saying the Creed, we should be taken by this movement and filled with a hope that has no bound – a hope of salvation, grounded in the intimate knowledge of Christ’s love.

Next time you read the Nicene Creed, feel the passion and the involvement it invites: from the very first “We believe” to the final agreement “Amen”.