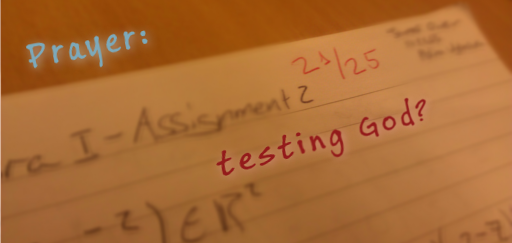

Being bold in prayer is tricky.

Don’t get me wrong: boldness in prayer and a faith to move the mountains are good things. There are also practical ways to increase boldness in prayer. But in all of that, there is a difficult balance to strike, between expecting our prayers to be answered and considering that as a right that we have come to acquire.

The danger is there, that we start demanding things from God, as though he were indebted to us, rather than the opposite. The Israelites did:

They tested God in their heart

by demanding the food they craved.

They spoke against God, saying,

“Can God spread a table in the wilderness?”

And God got angry at them for it.

I wouldn’t be quick to dismiss this as God being angry at some form of lack of faith on the part of the Israelites. Or to think that the Israelites wanted to make sure of God’s power before they went on and trusted Him. After all, they had all left Egypt on the basis of that faith, the power of God had just been shown them when they were thirsting for water.

Yes, their prayer was a test; but one that we can be led to put God to in our own prayer life, without noticing that we do. We test God in our prayers when we allow our faith to depend on the outcome of the prayer.

Expectant prayer becomes tricky, then: we want to both be bold in the assurance that God will provide, but we need to not let our faith depend on it. Prayer, and our relationship with God, cannot become a utilitarian thing. How do we achieve that, though?

In remembering that our prayer comes from faith and relies entirely on that faith. Yes, answered prayers can feed a little into faith; and both may grow together. But we must not allow ourselves to turn to a system where faith relies on answered prayers.

The Lord’s prayer, rightly, starts with a statement of praise of God. This is not only a statement of what is the most important, but also a way of giving us the right state of mind for prayer: one that looks at God first, and then allows us to respond and ask for our daily bread expectantly.

To conclude, though, let us remember that after being angered, God still provided the manna. He still answered the prayer, even when it did not rely on faith alone. Prayers born out of necessity, prayers born out of strife, or those where we doubt our own worth in God’s eye and therefore God’s answer – these are all acceptable. But let’s not make a habit of them ;-)